Michael's Life: Homo da Remo 1401-1406

On June 5 of 1401, a young man who called himself Michael of Rhodes enlisted as a common oarsman aboard a Venetian war galley visiting the Italian port of Manfredonia. We have no information as to when or how he got there, but from his name and the inclusion of Greek prayers in his manuscript, we can guess that he had recently arrived there from the island of Rhodes. Michael may have arrived in a sailing ship looking for grain, or possibly horses. If so, he had to jump one ship to join the other. What made him do it?

Michael never says, but the likely answer is that an ambitious young man took advantage of an opportunity to leave his homeland in the hopes of improving his station in life. We don't know Michael's social background; he may have been a slave, a peasant, or from one of the many Greek families of craftspeople, shopkeepers, or sailors on the island.

Rhodes was controlled by the crusading order known as the Knights of the Hospital, which had taken control of the island shortly after the last Crusaders had been ejected from the Holy Land in 1291. Centered on the increasingly vulnerable Byzantine Empire, the eastern Mediterranean in the early 15th century was a region of lively commerce and intense pressures exerted by various groups seeking to maintain and expand their influence on both land and sea. These groups included some from the Italian peninsula such as the Venetians and the Genoese, and others from the east such as the Ottoman Turks, whose leader Bayazed I had inflicted a crushing defeat on Western forces at Nicopolis in 1396, as well as the Mongols led by Timur.

In 1401 when Michael signed on to a Venetian ship, Venetian manpower shortages during a time of naval and commercial expansion meant that numerous Greeks and other foreigners traveled from lands further east to Venice to find employment as oarsmen in Venetian galleys. Venice needed oarsmen in this period, and a recent agreement between it and the Grand Masters of Rhodes had forbidden Venetian captains to pick up sailors there, because of the great number of slaves that had been signing onto Venetian ships in Rhodes. What made Michael's career different from that of the many foreigners who signed on to Venetian galleys was the fact that he rose from the ranks of the oarsmen to high shipboard offices usually held only by native-born Venetians.

Tasks of the homo da remo

Michael must have had good reasons for enlisting as a homo da remo in the Venetian navy, for the life of an oarsman was one of backbreaking labor in appalling conditions.

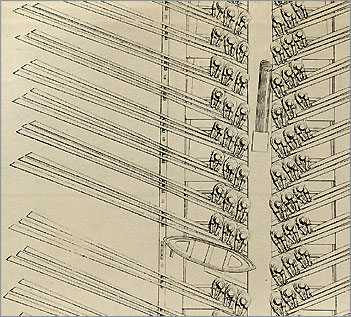

For starters, an oarsman like Michael was just one member of a crew of approximately 215 men crammed into a ship around 120 feet long, 20 feet wide, and 10 feet deep. Each man sat with two other oarsmen on benches arranged along each side of the main deck. There were normally 30 benches and 180 oarsmen on board. With so many men and so little space, there was no room to move around. The oarsmen were forced to stay at their benches all day and sleep there at night. Fully exposed to the elements, they had to endure drenching rain, brutal cold, and scorching heat for hours and sometimes days on end.

The oarsmen rowed according to a system called a sensile, meaning that each man on a bench pulled his own oar. While each oar was slightly different in length, all were extremely heavy, averaging 26 feet in length and weighing approximately 132 pounds.

Each stroke began with the oarsmen sitting on their benches facing the stern of the galley, holding their oars out of the water. The oarsmen then rose from the bench together, stepping onto a low footboard below them. Bracing one foot against the footboard, arms straight, they pushed the end of the oar toward the stern, bringing the oar blade forward. As they pushed, the oarsmen placed their second foot on the back of the bench in front of them. As the blade entered the water, they pushed off the bench with that leg and the footboard with the other, pulling with their backs as they basically fell onto their bench. The oars came out of the water and the stroke was completed. The process was too draining to be sustained for long: The oarsmen normally completed only two strokes in succession, then skipped a stroke to regain their strength for the next two pulls.

To conserve their strength and stave off exhaustion, normally only half the oarsmen rowed while the other half rested. A day's voyage started sometime between 2:00 and 5:00 in the morning and ended in the early afternoon, to spare the men the worst heat of the day. The galley's lateen sails were used whenever possible, but records suggest that oars were used for fully one-quarter of every voyage. That was a great deal of rowing on a journey from Venice to London or Alexandria.

The abysmal living conditions of oarsmen could be made much worse by their diet, the quality of which depended on the extent to which extra provisioning could be provided at ports of call. Without such supplements, a typical breakfast consisted of hard-bread ship's biscuit and beans. The second meal of the day consisted of more biscuit, this time boiled in oil to make bread soup, and perhaps a little cheese. On rare occasions the men might be allowed a little wine. Seldom did they get any meat. The oarsmen's diet supplied 3,000 to 3,500 calories a day. Unfortunately, since the tin can had not yet been invented, biscuit was stored in canvas bags, where it quickly became rotten or infested with weevils. Similarly, there was no way to keep water fresh or sealed against insects. It quickly became foul-tasting and brackish.

This monotonous diet could wreak havoc on the digestive systems of men stuck on their benches, unable to move around. Beans triggered gas or bloating. Too much biscuit caused constipation; rotten biscuit led to diarrhea. If fresh fruit could not be made available, the result was scurvy, so teeth could fall out on a long voyage. Other vitamin deficiencies could cause inflammation of the nerves or paralysis of the lower extremities (beriberi), as well as skin lesions, diarrhea, or even dementia (pellagra).

The fact that Michael survived six years as an oarsman and more than 40 voyages in these kinds of conditions is a testament to his incredibly strong physical constitution.

Military voyages

The first ship Michael joined was a military galley belonging to the Venetian navy, or Guard. The Guard fleet had various duties. One was to protect Venetian possessions in the Adriatic and Aegean Seas. Another was to protect Venetian merchant ships, especially the merchant galley convoys sailing down the Adriatic to destinations such as Constantinople, Beirut, and Alexandria. The Guard was also charged with searching for the seemingly endless number of pirates prowling the eastern Mediterranean.

A typical Guard squadron consisted of four or five ships, the crews of which represented a mobile fighting force of 800 to 1,000 men. But not all of the fighting took place at sea. The crews included archers, and oarsmen and archers alike were often deployed as marines in assaults on coastal towns and fortresses. Michael himself was involved in a great deal of fighting while serving in the Guard.

Michael's very first ship, captained by the famous Venetian commander Pietro Loredan, provides an example of the kind of service he would see. A member of one of Venice's most prestigious families, Loredan had been sent to Manfredonia to ensure the security of Venetian grain ships trading in the area. Two months after Michael joined the crew, his ship was ordered to Corfu to help fight Ladislaus of Anjou, king of Naples, for control of the island that was an important base for Venetian shipping. Michael soon found himself in Crete (Candia), then back in Modone. It was late autumn before his ship returned to Venice.

Two years later, in 1403, Michael was involved in a protracted naval campaign that ended with a major sea battle against the Genoese. Michael refers to this event as "the time we broke Pozichardo (![]() 90-2b)." Pozichardo was the Venetian name for the French knight known as Marshal Boucicault, a famous soldier of the time who had become governor of Genoa.

90-2b)." Pozichardo was the Venetian name for the French knight known as Marshal Boucicault, a famous soldier of the time who had become governor of Genoa.

Genoa and Venice were long-standing enemies, having fought three major wars in the previous century and a half. In late 1402, the Venetians learned that Boucicault was preparing a large fleet, supposedly headed for Cyprus to crush a rebellion. Some Venetian merchant ships had already been seized there by the Genoese, so tensions were already rising when the Venetians realized that Boucicault's fleet was far too large for a simple invasion of Cyprus. They worried that he would attack the Byzantine Empire, lands belonging to the sultan of Egypt, or Venetian possessions in the Aegean—all of which would have had a detrimental effect on Venetian trade.

In March 1403, Venice dispatched a Guard fleet commanded by the famous Venetian captain of the fleet Carlo Zeno, with orders to prevent the Genoese from attacking any Venetian possessions or seizing Venetian ships and goods. Michael sailed in a galley under the command of sopracomito Andrea da Molin.

To make a long story short, the Venetian fleet shadowed Boucicault all the way to Rhodes, then returned to its normal patrol routes. Boucicault never did attack Cyprus, launching instead a series of raids on Muslim cities along the coast of the Middle East. On August 10, Boucicault's forces attacked Beirut, not only seizing Venetian ships in the harbor but pillaging Venetian warehouses in the city and burning them to the ground.

Word of this outrage reached Zeno on September 9. He immediately sent the ship of Andrea da Molin, with Michael aboard, to Venice for fresh orders. Meanwhile, he set out to find Boucicault, either to obtain reparations or do battle.

The fleets finally met on October 7, not far from Modone. The battle raged on for four hours, and for much of that time Zeno's flagship was grappled to Boucicault's. The fighting was brutal. Fortunes shifted back and forth, but eventually Boucicault fled. In the end, an estimated 600 Genoese were killed, and three Genoese galleys were captured along with 400 men. The Venetians lost some 300 men and one galley.

Michael's ship returned from Venice the next day, ironically carrying orders for Zeno not to engage the enemy. But if Michael missed the battle, he now witnessed the devastation of warfare at sea: the broken ships and oars; the thick blood of soldiers and seamen stabbed with swords or pikes, or shot with crossbows; the dead, the dying, and the wounded.

Michael himself would take part in numerous fights and battles during his career, but he served only once more in the Guard as an ordinary oarsman. He signed on as proder in 1405. The proder was a senior oarsman whose job was to teach new recruits how to row and sing out the cadence that helped the three men on each bench synchronize their stroke. It was a small sign of promotions to come.

Commercial voyages

Perhaps because of the carnage he witnessed in 1403, Michael tried something new in 1404, enlisting as an oarsman on a merchant galley bound for Flanders. It was the first time he participated in the famous Venetian system of merchant galley convoys, and the first of his many voyages to London and Bruges.

The convoys to Flanders were an excellent complement to Venetian trade with the Orient. In the East, the merchant galleys picked up high-value goods like silks and spices, particularly pepper, which were highly sought after in Northern Europe. In the West, they traded for the raw wool of England and particularly the fine woolens of Flanders, which were in demand throughout Italy, Greece, and the Middle East.

These convoys were especially profitable because of the sometimes chaotic political situation in Northern Europe during the Hundred Years' War. Constant fighting disrupted overland travel and upset the medieval system of annual trade fairs, making it lucrative to transport high-value goods all the way around Europe by water, rather than across the continent itself.

While there may not have been fighting, the voyage to Flanders was the longest, most arduous undertaken by merchant galleys. The four or five ships of the Flanders fleet left Venice in late April or early May when it was still cold. They sailed to Lisbon through pirate-infested waters. Then they left Lisbon for the English Channel, crossing the notoriously dangerous Bay of Biscay without touching land. Once in the Channel, two of the galleys went to London, Sandwich, or Southampton. The others sailed on to Sluys on the coast, and goods were taken by canal to Bruges in Flanders (now Belgium). After a few months of trading, the galleys set out on the return journey, arriving in Venice in late November, December, or even January.

Danger aside, the voyage to Flanders represented a moneymaking opportunity for Michael. In addition to their pay, merchant galley crews had the right to carry duty-free goods to trade for their own profit, a right known as the portata. The amount of each crew member's portata was determined by his rank. Accounts of galley voyages often mention impromptu trade fairs springing up whenever a merchant galley entered a port, with the crew hurriedly setting up tables to hawk their wares quayside.

Even if an oarsman decided not to trade on his own account, he could sell his portata to others or enter into several different kinds of loan and partnership arrangements concerning it. On his very first journey as a merchant galley oarsman, Michael was already involved in the kind of trade that relied heavily on the commercial mathematics that takes up the first half of his manuscript.

Michael enlisted as proder on a second journey with the Flanders fleet in 1406, this time going with the ships to London.

Find out more:

The best introduction in English to Venice in Michael's time is Frederic C. Lane, Venice, A Maritime Republic (Baltimore 1973). The most complete and up-to-date history of Venice is the multi-volume Storia di Venezia, published by the Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana since 1991, especially volumes 3 to 5 on the later Middle Ages and the Renaissance, and the special volume 12, Il Mare. For the Byzantine Empire, see Robert Browning, The Byzantine Empire, Rev. ed. (Washington, D.C., 1992); and Warren T. Treadgold, A History of the Byzantine State and Society (Stanford, CA, 1997). For the Ottoman Empire, see Kate Fleet, European and Islamic Trade in the Early Ottoman State: The Merchants of Genoa and Turkey (Cambridge, 1999); Colin Imber, The Ottoman Empire, 1300-1650: The Structure of Power (New York, 2002); Halil İnalcık with Donald Quataert. eds., An Economic and Social History of the Ottoman Empire, 1300-1914 (Cambridge,1994); and Donald Edgar Pitcher, An Historical Geography of the Ottoman Empire from Earliest Times to the End of the Sixteenth Century (Leiden, 1972). For the Balkans, see John V.A. Fine, Jr., The Late Medieval Balkans (Ann Arbor, MI, 1987).

Other studies of aspects of Venetian life in the period are:

- Stanley Chojnacki, Women and Men in Renaissance Venice (Baltimore, 2000).

- Robert Finley, Politics in Renaissance Venice (London,1980).

- J. H. Hale and M. Mallet, Military Organization of a Renaissance State: Venice c. 1400 to 1617 (Cambridge, 1984).

- John Martin and Dennis Romano, eds,. Venice Reconsidered: The History and Civilization of an Italian City-State, 1297-1797 (Baltimore, 2000).

- Dennis Romano, Patricians and Popolani: The Social Foundations of the Venetian Renaissance State (Baltimore, 1987).

- Alan M. Stahl, Zecca: The Mint of Venice in the Middle Ages (Baltimore, 2001)

< Introduction | Nochiero >