Ships and Shipbuilding: Toolkit

The Illustrated Galley of Flanders

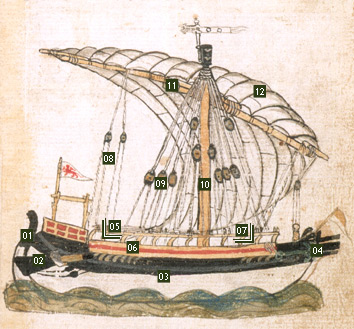

In Michael's introduction to the galley of Flanders, he says that he will not only tell you how to build the ship, but also how to equip it with everything it needs for sea. He goes on to describe in great detail the vast array of supplies and equipment required. He added a number of pictures as well, making this portion of the manuscript the first illustrated text on European shipbuilding we know.

01] Stern Rudders: In addition to traditional side rudders, the galley of Flanders was equipped with a stern rudder. Michael calls it a timon bavonescho, or a "Bayonne rudder." Venetian mariners thought the stern rudder originated in Bayonne, on the Atlantic coast of France. The picture shows the hardware used to hang the rudder on the sternpost.

01] Stern Rudders: In addition to traditional side rudders, the galley of Flanders was equipped with a stern rudder. Michael calls it a timon bavonescho, or a "Bayonne rudder." Venetian mariners thought the stern rudder originated in Bayonne, on the Atlantic coast of France. The picture shows the hardware used to hang the rudder on the sternpost.

[back to top]

02] Side Rudders: Michael shows the galley of Flanders with side rudders. He calls them timony latiny, or "Latin rudders." These rudders hung on the stern quarters and were used to steer on the same principle as the paddle of a canoe. The picture shows a square hole where the tiller assembly fit into the side rudders.

02] Side Rudders: Michael shows the galley of Flanders with side rudders. He calls them timony latiny, or "Latin rudders." These rudders hung on the stern quarters and were used to steer on the same principle as the paddle of a canoe. The picture shows a square hole where the tiller assembly fit into the side rudders.

[back to top]

03] Hull: Galleys were constructed "on the stocks," which means that they were constructed on land and had to be propped up to keep them from falling over. Here, Michael shows the completed hull. The black dots on the hull indicate the wooden treenails, or pegs, that were used to fasten the planks to the frames.

03] Hull: Galleys were constructed "on the stocks," which means that they were constructed on land and had to be propped up to keep them from falling over. Here, Michael shows the completed hull. The black dots on the hull indicate the wooden treenails, or pegs, that were used to fasten the planks to the frames.

[back to top]

04] Anchors: Anchors were among the few items a galley came equipped with from the Venetian Arsenal, where the ships were built. Michael says the galley of Flanders needed five anchors, each weighing 120 pounds, or 600 pounds total.

04] Anchors: Anchors were among the few items a galley came equipped with from the Venetian Arsenal, where the ships were built. Michael says the galley of Flanders needed five anchors, each weighing 120 pounds, or 600 pounds total.

[back to top]

05] Boats: Each galley carried two boats. The larger barcha and the smaller chopano were essential pieces of a ship equipment. According to Michael, some galleys also carried a gondola.

05] Boats: Each galley carried two boats. The larger barcha and the smaller chopano were essential pieces of a ship equipment. According to Michael, some galleys also carried a gondola.

[back to top]

06] Outrigger: Michael doesn't provide a separate picture of the outrigger on which the oarsmen rested their oars. Instead, he represents the outrigger in his illustration of a galley of Flanders under sail. The short, upright pieces are the schermi, or thole pins, which functioned as oarlocks.

06] Outrigger: Michael doesn't provide a separate picture of the outrigger on which the oarsmen rested their oars. Instead, he represents the outrigger in his illustration of a galley of Flanders under sail. The short, upright pieces are the schermi, or thole pins, which functioned as oarlocks.

[back to top]

07] Capstan: Raising anchors, loading cargos, and lifting masts and yards often required more strength than the crews could humanly provide. A capstan combined with block and tackle and pulleys was essential for heavy lifting jobs.

07] Capstan: Raising anchors, loading cargos, and lifting masts and yards often required more strength than the crews could humanly provide. A capstan combined with block and tackle and pulleys was essential for heavy lifting jobs.

[back to top]

08] Rope: Thousands of meters of rope were needed for block and tackle, rigging, anchors, and cables. Michael describes a bewildering assortment of ropes, which varied according to the weight per foot and the number of strands twisted together.

08] Rope: Thousands of meters of rope were needed for block and tackle, rigging, anchors, and cables. Michael describes a bewildering assortment of ropes, which varied according to the weight per foot and the number of strands twisted together.

[back to top]

09] Rigging: Every sailing ship required standing rigging to hold up the masts and yards and running rigging to operate the sails. Almost all the lines used for running and standing rigging in a galley involved some combination of block and tackle.

09] Rigging: Every sailing ship required standing rigging to hold up the masts and yards and running rigging to operate the sails. Almost all the lines used for running and standing rigging in a galley involved some combination of block and tackle.

[back to top]

10] Masts: Michael shows only one mast on his galley of Flanders. In the text, he points out that each galley carried two, a mainmast in the middle and smaller mast aft. The masts were held in place by a square mast step resting on the keel.

10] Masts: Michael shows only one mast on his galley of Flanders. In the text, he points out that each galley carried two, a mainmast in the middle and smaller mast aft. The masts were held in place by a square mast step resting on the keel.

[back to top]

11] Yards: The galley's lateen sails hung from huge yards, called antenne, which were composed of two or more shorter yards lashed together. This enabled the sailors to make yards that were longer than the galley itself, but which could still be stowed inboard.

11] Yards: The galley's lateen sails hung from huge yards, called antenne, which were composed of two or more shorter yards lashed together. This enabled the sailors to make yards that were longer than the galley itself, but which could still be stowed inboard.

[back to top]

12] Sails: Galleys were equipped with large, triangular lateen sails and carried a variety of different sails for different wind and weather conditions. The sails were made from many square pieces of cloth sewn together. Michael writes at length about the size and construction of different sails.

12] Sails: Galleys were equipped with large, triangular lateen sails and carried a variety of different sails for different wind and weather conditions. The sails were made from many square pieces of cloth sewn together. Michael writes at length about the size and construction of different sails.

[back to top]